The smoke has cleared from fires that raged in the Amazon in August and September, darkening skies and making headlines around the world.

Now, science and policy experts at Conservation International and elsewhere are sifting through the ashes, looking for patterns and working on a number of fronts to prevent future fires — and prevent the Amazon biome from pitching over the dreaded “tipping point,” at which the world’s largest rainforest would mutate irrevocably into scrubland.

Here are three takeaways from our work.

- Deforestation fueled the fires: Many of the fires occurred in areas that had been recently deforested.

- Protected areas work: Most of the fires occurred outside the boundaries of the many protected areas in the Brazilian Amazon.

- The world is responding: Despite the political climate in Brazil, public attention has accelerated a host of new efforts that are offering reasons for hope.

First go the trees, then comes the fire

August and September are typically “fire season” in the southern Amazon, when relatively drier conditions prevail, and farmers prepare to plant their crops. This year’s fires were set mostly on private lands, and mostly for the purposes of expanding production of soy and beef, two of Brazil’s main agricultural products.

“The process of deforestation in the [Brazilian] Amazon is mostly the same,” said Mauricio Bianco, vice president of Conservation International in Brazil. “First the big, valuable trees are taken out and are sold on the black market. Then the smaller trees are cleared and pasture put down, by burning the land.”

So, what was different about the Amazon fire season in 2019? The number of fires was up sharply from the previous year: 60 percent more fires this August than in August 2018, according to Daniela Raik, who leads Conservation International’s work across South America.

At least part of the reason for the spike in number and intensity of this year’s fire season, experts believe, is that more of the fires occurred in places that had been completely or partially deforested, drying these areas and enabling burning.

(Video courtesy of Matthew Finer/Planet Labs Inc.)

The time-lapse video above shows an area in Mato Grosso state in Brazil. The first frames show a mostly forested region in 2018; the ensuing frames show deforestation in May through August of 2019, and then fires to prepare the land for agriculture.

“We know that there has been an increase in deforestation in the last couple of years in the Amazon,” said Karyn Tabor, senior director of ecological monitoring in Conservation International’s Moore Center for Science. “And when there is more deforestation, there are going to be more fires.”

Protected areas work

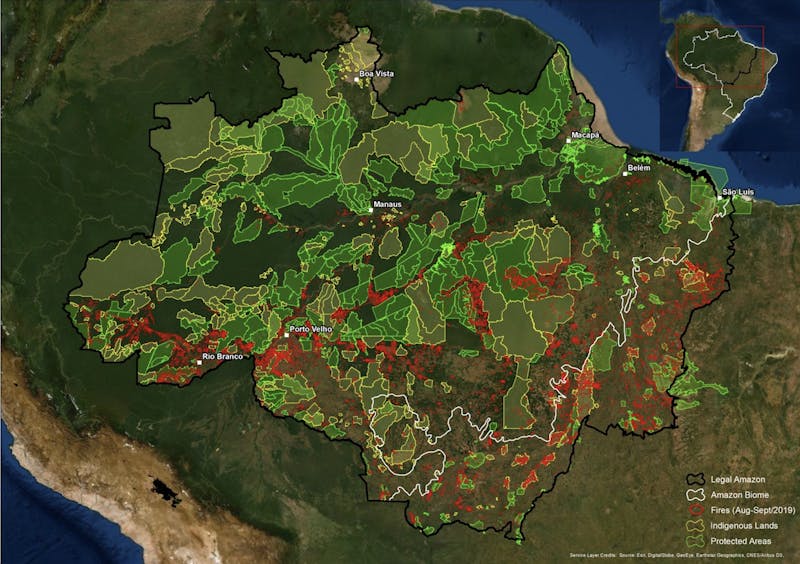

Maps of the fires revealed a clear and undeniable trend: For the most part, Brazil’s protected areas (including indigenous lands) saw very few fires. In many cases, fire extent stopped right at their boundaries.

In the above map of the Brazilian Amazon, red dots represent fire events in August and September 2019, as recorded by satellite data. Green and yellow shaded areas represent protected and indigenous territories. With some exceptions — particularly in the southern and eastern parts of the Amazon basin where much of the burning occurred — protected areas were unscathed.

“You can see it clearly — these protected areas acted almost as a barrier to the fires,” Bianco said.

Protected areas remain one of the most important tools for conservation, with enormous potential to protect against climate breakdown and the loss of wildlife — while enabling indigenous and local communities to continue to sustainably prosper from the benefits that nature provides. Conservation International has worked in the Amazon for decades to help establish more of these areas.

The problem: Protected areas are not forever.

The past few years have seen a wave of rollbacks in legal protections for protected areas, including in Brazil, research from Conservation International has shown.

A study earlier this year found that 4 percent of the country’s protected areas were legally downgraded or reduced in some way — and these events tend to go hand in hand with deforestation.

“Protected areas in Brazil that were already more deforested were at greater risk for experiencing legal rollbacks of their protections,” Conservation International’s Rachel Golden Kroner, a global expert on the legal loss of protected areas, told Conservation News in August.

“With this in mind, more forest loss due to fires could lead to more [of these] events.”

An ounce of prevention

Securing protected areas, then, is critical for preventing future fires.

“We are not in the business of putting fires out on the ground, but we are in the business of preventing fires,” Raik said. “So if we want to prevent the fires, we need to conserve the forests.”

A tool called Firecast, developed years ago by Conservation International, is helping to do that. Firecast, an open-access online platform, uses satellite observations to track ecosystem disturbances such as fires, fire risk conditions, deforestation and delivers that information to decision-makers.

- FIRES IN AMAZONIA: Click here for monitoring and analysis of the fires in real time

“Early-warning systems like Firecast are just such a game-changer for South America because, unlike in the U.S., there are very little resources allocated to fight fires,” Tabor said. While the U.S. budgets billions of dollars a year to fight wildfires, where fires are a normal ecological phenomenon, fires do not naturally occur in the Amazon rainforest, and there is limited budget and equipment to fight them, Tabor says.

This makes it that much more critical to prevent fires by improving fire management, investing in early warning systems and preventing deforestation from taking place, she said.

The world is watching

Fire season is not new to the Amazon. The intensity of global attention to the fires this year, however, is.

“I’ve never seen so much attention for the Amazon in Brazil,” Bianco said. “Never. Not even in 1992, when we had the [UN climate conference] in Rio.

“This year we had, for two straight weeks, in the media, on the covers of magazines, on the news on TV — everyone was talking about the Amazon.”

Outside Brazil, the reaction was just as intense, and has swiftly translated into action.

Major global brands took note, with companies such as VF Corporation and H&M announcing last month that they would stop buying Brazilian leather until they were confident that their purchases were not contributing to deforestation in the Amazon.

On a more uplifting note: the signing in September of the Leticia Pact, a South American-led agreement among seven of the nine Amazonian countries to address deforestation, fires and sustainable development in the world’s largest rainforest. Later that month, Conservation International and the government of France committed more than US$ 100 million to support the implementation of the pact.

And in a case of extraordinary — one could even say divine — timing, a long-planned and historic gathering of religious leaders and indigenous peoples kicked off in the Vatican this month. Pope Francis opened the three-week meeting at the Vatican, known as a synod, by urging members of the Catholic Church to protect the Amazon. More than 180 cardinals, bishops and priests are working with indigenous peoples from several tribes across South America to address, among other things, humanity’s “ecological sins” against the forest.

If 2019 is a turning point for the future of the Amazon, major questions remain: What effects will the global trade in soy and beef have on the Amazon? How secure are Brazil’s protected areas — and indigenous rights? Will the Leticia Pact stick?

Whatever happens, the fires and the attention they’ve galvanized provide “an incredible opportunity for groups like Conservation International to make a difference in the Amazon,” said Raik, “even under these very challenging times.”

Bruno Vander Velde is the senior communications director for Conservation International.

Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates here. Donate to Conservation International here.

Cover image: A bird’s eye view of the stark contrast between the forest and agricultural landscapes near Rio Branco, Acre, Brazil. (© Kate Evans/CIFOR/Flickr Creative Commons)

Further Reading: